e.g. a new processor processor fed with ‘NOP’s

Consider an ALU in a pipelined processor design. This performs a given set of operations, typically one per clock cycle although pipeline stalls and flushes may interfere with this. May want to check:

Each test is simple in itself but they can be numerous, even in a ‘simple’ unit! It is likely that this list is not exhaustive.

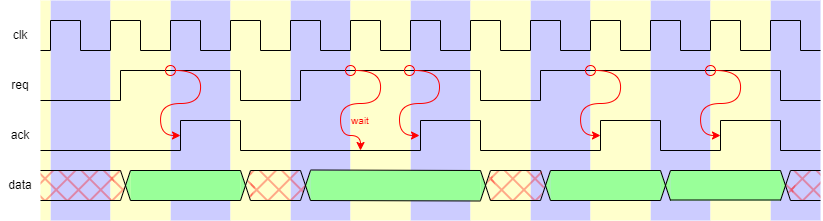

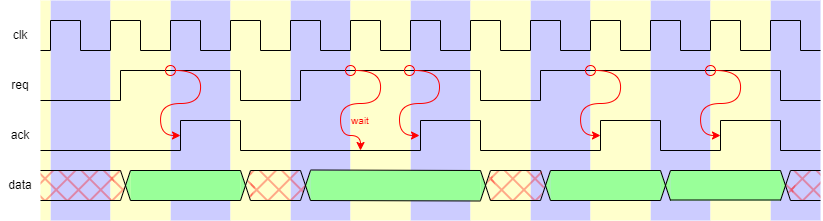

In the laboratory system the pixel output interface from the drawing engine has the following timing rules.

There are two control signals {req, ack} with an associated bundle of data. Following an active clock edge:

In the figure:

Notes:

Do the tests cover all these cases?

Is (for example) the data held stable when the second transfer waits?

Just because a design runs through appropriate control sequences this doesn't mean that the output data is correct.

In an RTL abstraction the details of the ‘data’ are not really considered. However it is important to check that the data are also correct.

If control signals are interacting correctly the data can be checked. Probably the first thing to establish is that the data is stable when it is expected to be. It is not much use if a pipeline's control signals stall correctly but the data tries to keep flowing.

The data can be sampled for correctness at the time an interacting unit would do so. This requires some expected results for comparison, which could be generated in a HDL test harness or imported from another model. Note that the expected results should have been verified in some way.

Data crossing interfaces should be deducible (if not directly available) in a higher level model. Such a model can be used in various ways to aid testing.

A high-level model may also be able to generate internal variable sequences with little extra effort.

It is possible to test some units exhaustively, i.e. try every possible case. These are usually combinatorial units as each bit of buried state doubles the number of tests required.

Example: 8 × 8 multiplier blockThere are 2(8+8) = 65536 possible input combinations. It is quite feasible to test this and it is possibly the simplest thing to do.

Counterexample: 32 × 32 multiplier block

There are 2(32 + 32) = 18446744073709551616 possible input combinations.

Checking at one per nanosecond would still require over 500 years to complete.

Exhaustive tests are feasible for control circuits, not for (most) data.

If exhaustive testing is impossible some sample data are needed. There are various ways of generating these:

Each method has merits and drawbacks. Example: a set of random inputs to a divider may be unlikely to test the ‘divide by zero’ case. Random inputs could be biased so that (for example) small numbers are more likely if a block which counts leading zeros is under test.

Timing checks require some more detail in the model. Logic timings are difficult to estimate at an early simulation stage; however there are some timing checks which it may be worth modelling early.

A good example is reading a memory. On the laboratory board there is external SRAM to provide capacity for the frame buffer. This SRAM has an access time of 55 ns – which is more than one clock period (40 ns). A simple HDL RAM model might supply data as soon as the address was valid. In this case the data could be latched (accidentally) after one cycle and appear to work.

Even more worryingly, the 55 ns is a worst-case time; a real SRAM device may meet the 40 ns deadline … under some conditions. This could lead to many field failures, e.g. when the weather warms up or the battery is below half charge.

A more sophisticated model, which forces data ‘unknown’ until the relevant time has elapsed, would expose this fault because the ‘unknown’s would be latched and propagated.

Although it may not be possible practical to predict units'

timing relationships, even on a cycle-by-cycle basis, it may be useful

to monitor some sequence properties for verification.

Examples:

Back (up) to testing.

Forward to test coverage.