Puzzle and answer

The puzzle

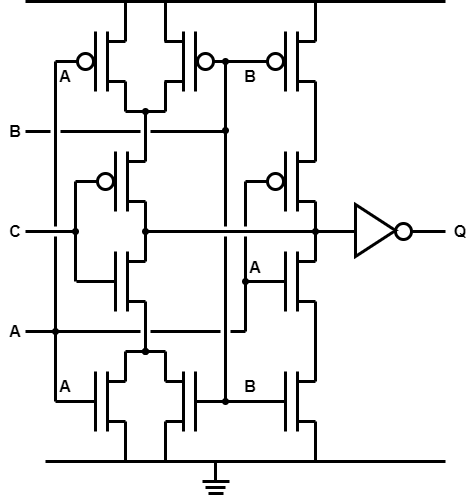

This figure shows the transistor-level schematic of a specialised

structure based on a complex gate and optimised to exploit

common inputs. It has only two series transistors in each

‘tree’. Fewer series transistors ⇒ smaller

(width) transistors ⇒ less capacitive load.

In increasing order of difficulty, can you:

- Deduce the truth table.

- Identify a credible (familiar?!) application.

- The input labelled ‘C’ has a lower input load than the other

inputs (only two transistors): how may this be exploited?

The answers

1. This is the truth table.

You can reason like this:

IF ((A == 0) & (B == 0)) THEN Q := 0

OR IF ((C == 0) & ((A == 0) | (B == 0))) THEN Q := 0

ELSE Q := 1

Note the output inverter, which also gives good output

‘drive’.

| A | B | C | Q |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

2. From the truth table it should be apparent that this is

a majority gate — i.e. its output is “1’ when

at least two (i.e. most) of its inputs are “1’.

An application you should have met before is carry generation

in a full adder.

3. If used as a component in an adder, the critical path

runs through the carries. Using “C’ for the carry (clue

in the label!) will make this slightly faster than “A’ or

“B’ which have double the input load.

The cell, as a whole, is implementing: Q = (A & B) | (A & C) | (B & C)

which could be done with an AND-OR-INVERT but we've optimised and

saved <how many?> transistors

and kept the maximum logic tree depth to two series

transistors <instead of?>.