These pages are provided as a brief aide memoire. There are many books and web tutorials which give a more complete description. A suggested, on-line tutorial may be found at: http://www.asic-world.com/verilog/

The full standard (IEEE Std 1364-2001) is available via IEEE Xplore (via the Library subscription) — and, possibly, in other places.

This not meant to be comprehensive – it should be a reminder of some common constructs; you may meet some new material later!

| Syntax | Use |

|---|---|

| wire aaa; | A simple, combinatorial logic variable. |

| reg bbb; | A variable which may (or may not) be state holding. |

| reg [7:0] ccc; | As above, but an eight bit value. |

Operators are, in general the same as in C or Java. There are some additional features:

| Syntax | Use |

|---|---|

| >> | Right shift (logical) |

| >>> | Right shift (arithmetic, if applicable) |

| &ccc | A (unary) reduction operator; ANDs all the bits in the variable together. Others include ‘|’, ‘^’, ‘~&’ etc. |

| {ddd, eee} | Concatenate two (or more) variables. |

| {4{fff}} | Concatenate four copies of fff. |

| Syntax | Use |

|---|---|

| initial | Execute following statement once, starting at time = 0. |

| always | Run following statement continuously. (Needs some form of delay!) |

| always @ (…) | Run following statement whenever an event in the parenthesized list occurs. |

| Syntax | Use |

|---|---|

| #20 | Wait for 20 time units. |

| @ (posedge clk) | Wait for a (rising edge) event on signal. |

| Syntax | Use |

|---|---|

| 1234 | A decimal number. |

| 16'hABCD | A 16-bit hexadecimal number. |

| 4'b1010 | A 4-bit binary number. |

| x ('hx etc.) | The ‘unknown’ value. |

| z | The high-impedance state. |

| Syntax | Use |

|---|---|

| assign a = b + c; | A continuous assignment; combinatorial logic. Assigns to wire. |

| d = e & f; | Blocking assignment. d may be reassigned in block,

reading top-to-bottom. Use for combinatorial logic. Assigns to reg. |

| g <= h; | Non-blocking assignment. g should be assigned at most

once at any time. Use for registers. Assigns to reg. |

For synthesis (at least!) only assign to each variable in one block. (If you are writing combinatorial code with blocking assignments you can reassign a variable within that block in a similar manner to software programming.)

| Syntax | Use |

|---|---|

| if (…) … {else} … | C/Java like choice. |

| case | Multi-way ‘switch’ choice. |

| repeat (10) | Perform following statement ten times. |

| while (…) … | C-like repetition. |

| for (…;…;…) | C-like repetition. |

Some of these constructs are useful for testbenches but are not synthesizable.

initial clk = 1; // Set clock initial value

always #5 clk = !clk; // Oscillate with 10 unit period

initial #1000 $stop; // Limit simulation run time

initial

begin // Bracket following into one statement

reset = 1'b1; // Initialise the Device Under Test

en = 1'b1; // Set up an initial input value

@ (posedge clk) // Wait for next rising clock edge

reset = 1'b0; // Remove reset

while (c == 0) @ (posedge clk); // Wait until output 'c' asserted

en = 1'bx; // Make input 'en' undefined

end // End of statement (but time continues)

This testbench assumes the existence of some design which has defined the variables. It is reminiscent of the stimulus files used in testing in Questa.

In the example above there are four separate blocks. The three ‘initial’ blocks start at time = 0 and run once. Thus the first statement initialises an input and stops. The other ‘initial’ statements contain delays which can deschedule them for periods of (simulation) time.

The ‘always’ block has no sensitivity list so it runs immediately. A conflict with the preceding ‘initial’ assignment is avoided by the delay. Following the delay the clock is inverted and the always runs again; thus the clock oscillates. The second ‘initial’ block waits for a (long) time and then tells the simulator to halt. Without this the simulation would run forever – or until it is halted by user intervention.

Note: it would be a mistake to write something purely like:

always clk = !clk;

Combinatorial logic loops like this (usually somewhat more subtle involving chains of signals) are quite common mistakes. We've added a page of description of the simulation process to help understand what happens.

The method shown is not the only way to achieve the desired effect. For example the clock (and termination) may be produced by:

initial

begin

clk = 0;

repeat (200) #5 clk = !clk;

$stop;

end

You may prefer this style.

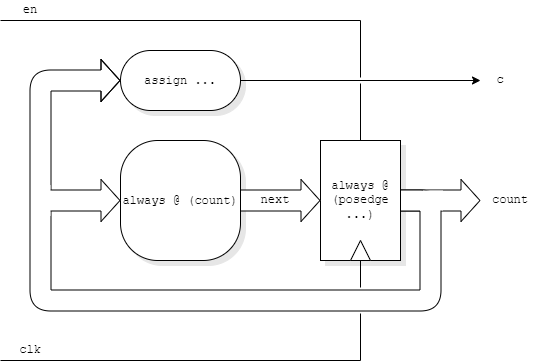

module counter (input wire clk, input wire en,

output reg [3:0] count, output wire c);

reg [3:0] next; // Internal variable (combinatorial)

always @ (count) // Run block when ‘count’ changes

begin

next = count + 1; // Blocking assignment

if (count == 9) next = 0; // Variable may be reassigned

end

always @ (posedge clk, posedge reset)

if (reset) count <= 0; // Asynchronous reset

else if (en) count <= next; // Maybe adopt new value (non-blocking)

else count <= count; // This clause may safely be omitted

assign c = (count == 9); // TRUE is a ‘1’ value

endmodule

The example is contrived to illustrate a number of different Verilog features.

‘next’ is sometimes reassigned in its block but it is always assigned, thus the combinatorial block always calculates its result(s) from its input(s). This guarantees it is combinatorial and does not need any state holding. (See note below).

The description of the register, with its asynchronous clear, is one which will be recognised by the synthesizer.

The register (‘count’) does not need the second else; if it is not enabled it will do nothing. There is already a state-holding element here so this doesn't affect the circuit.

The carry output (‘c’) is assigned combinatorially from a comparator. In practice this may ‘glitch’ as its input bits change. This doesn't matter as long as it's only sampled on a clock edge. It should not be used as a clock, itself.

It is also possible, and sometimes clearer, to incorporate some of the logic in the same statement as the register assignment.

always @ (posedge clk, posedge reset)

if (reset) count <= 0; // Asynchronous reset

else if (en)

if (count == 9) count <= 0;

else count <= count + 1;

The choice of style can depend on the author. This is shorter than the previous example (above) although the variable ‘next’ or equivalent – the state that is about to be entered – is sometimes a convenient input for other logic … or for viewing for debug purposes.

Because Verilog is a Hardware Description Language it acts like a programming language: if a variable is not being defined (at any time the thread is run) then it retains its previous value. In a hardware realisation this implies there must then be a storage element. In many cases this is not what is wanted in a synthesized design.

A logic synthesizer will usually spot the problem and produce a ‘WARNING’; unfortunately may people tend to ignore warnings.

Some ‘features’ of Verilog are open to abuse. It is possible to write Verilog code in numerous ways. Some ways are error-prone; they ‘look’ right but behave oddly, or are unduly expensive to build. Some models will run on a simulator. Some will run on particular simulators, but not on others. Some will run when synthesised into hardware. Some will be reliable across all tools and implementations.

Here are some guidelines to help you achieve the last of these cases.

If you have more simple, useful recommendations, do share them!

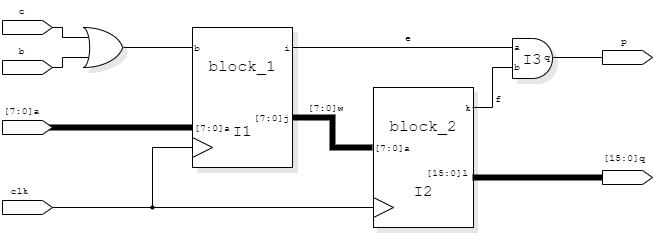

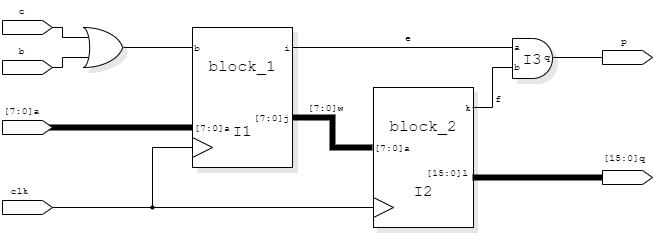

Verilog can also be used to specify hierarchical designs.

Example

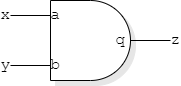

and2 gate_1 (.a(x), .b(y), .q(z));

where

and2 is the part (module) name

gate_1 is the instance name

{a, b, q} are the inputs/output of the module

{x, y, z} are wires at the higher level

Structural Verilog allows the explicit inclusion of certain cells within a design. The example below shows a simple module with a schematic equivalent.

module demo (input wire clk,

input wire [7:0] a,

input wire b,

input wire c,

output wire p,

output wire [15:0] q);

wire d, e, f;

wire [7:0] w;

assign d = b || c;

// Synthesizable statement

block_1 I1(.clk(clk), .a(a), .b(d), .i(e), .j(w));

block_2 I2(.clk(clk), .a(w), .k(f), .l(q));

and2 I3 (.a(e), .b(f), .q(p));

endmodule

This example is contrived to show some features:

Assume we have a module declaration:

module and2 (input a, input b, output q);

The Verilog 2001 syntax

and2 gate_1 (.a(x), .b(y), .q(z));

explicitly connects wires/buses to ports on the module by associating their

names. The order in which these are written is irrelevant. Ports may be omitted

(although this is only sensible for outputs; inputs should always be defined).

Verilog 1995 syntax relies on ordering:

and2 gate_1 (x, y, z);

…

Backwards compatibility means that Verilog 2001 will accept either.

It is suggested that the later syntax is preferred because it

is more robust against later edits, e.g. if another port is added to a

module.

Verilog is a Hardware Description Language but, if a subset of its

features are used, the description can be turned into an

implementation.

Just as a compiler takes a high-level language description of an

algorithm and turns it into machine instructions for a chosen

instruction set, a Verilog synthesizer turns a hardware description

into an underlying technology.

The technology will vary according to what is on offer on the target

process. Cell libraries are usually available from the

silicon foundry.

A typical cell library will contain familiar gates such as AND2, AND3,

OR2, … [and more - but more on that later].

During synthesis structures are identified in the source – and

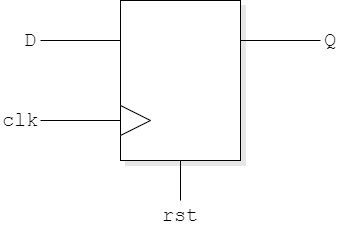

sometimes this fails. The lower right of the figure above shows a D-type

register with an asynchronous clear. Reassure yourself that you

follow the behaviour of this code.

Here's a genuine example we found with one synthesizer:

always @ (posedge clk, posedge rst)

‘rst’

is an asynchronous reset: a change of this signal will

‘run’ the block.

It is not uncommon to have asynchronous resets to

flip-flops/registers, as in “Stop what you're doing right

now!” This is okay as the reset becomes active.

However, in such circumstances, it is important that the

reset inactivation is coordinated with the clock, otherwise

there could be a timing violation (see later notes) and parts of a

system may be held in reset whilst others start running again. This

can lead to unpredictable behaviour: not a Good Thing.

Behaviourally these blocks are the same. They should simulate in the

same way. However the author needed to separate the asynchronous

input explicitly for synthesis.

When synthesizing for an FPGA the tool will look for structures it

can recognise and try to map these into the available resources.

Examples:

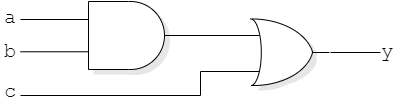

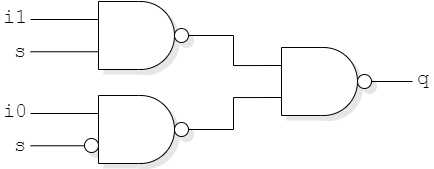

Synthesis: (possible) examples

assign y = a & b | c;

assign q = s ? i1 : i0;

always @ (posedge clk, posedge rst)

if (rst) Q <= 0;

else Q <= D;

C compiler

Verilog

Syntax parsing Syntax parsing

Semantic Analysis ‘Elaboration’

Optimisation Optimisation

Code dump Technology mapping

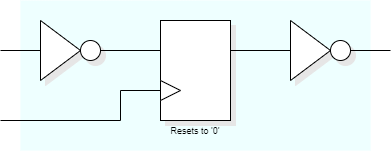

if (rst || clr) Q <= 0; // Failed to synthesize

else Q <= D;

always @ (posedge clk, posedge rst)

if (rst) Q <= 0;

else if (clr) Q <= 0; else Q <= D;

‘clr’

is an additional, synchronous reset; since it is only to be checked

at active clock edges it is not in the sensitivity list.

Note on resets

FPGA …

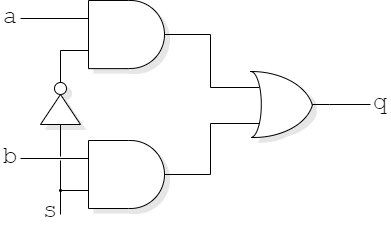

? s a b q

x 0 0 0 0

x 0 0 1 0

x 0 1 0 1

x 0 1 1 1

x 1 0 0 0

x 1 0 1 1

x 1 1 0 0

x 1 1 1 1

Logic functions will then be amalgamated to fit into LUTs of the appropriate size.

If a statement cannot be mapped into an available structure then the design may not fit the FPGA.

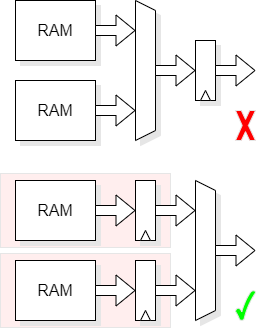

On the right are two RAM read structures. The upper one does not map to Xilinx block RAMs and therefore the RAM will be expanded into (a LOT of) combinatorial logic.

The lower structure looks bigger but exploits the available

resources and thus is (much) more efficient.

Back (up) to Verilog

Forward to more Verilog notes