Clock Domains ☆

Synchronous design is a Good Thing

- Simplifies RTL design

- May be easier to think about state diagrams

- Simplifies debugging – can take a ‘global’ view

of state

- Tool chains optimised for such

However it is not always possible to have one clock across an SoC.

- Synchronous clock distribution increasingly difficult.

- Blocks may work optimally at different frequencies:

- May be IP from different vendors

- Some I/O may require specific frequencies.

Metastability

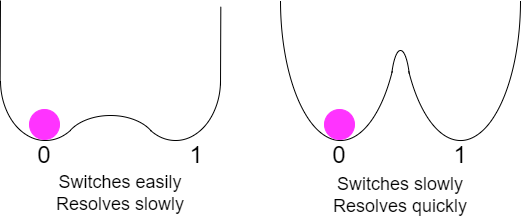

A model flip-flop: ball rolling between wells.

- The flip-flop has three stable positions: ‘0’,

‘1’ and a metastable position

‘half-way’

between. (There must be a flat

‘summit’ somewhere.)

- Violating set-up/hold conditions can result in the flip-flip entering

the metastable state.

- In principle the flip-flop can stay metastable indefinitely

- but if it starts to resolve one way, positive feedback pushes

it further in that direction.

- The probability of remaining metastable decreases

exponentially with time.

The dangers in a metastable state lie in that it can be interpreted as

different values by different inputs, or at different times. A

possible metastable flip-flop should only go to one place.

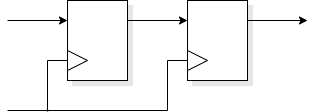

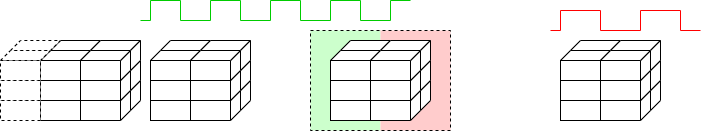

Synchronisers

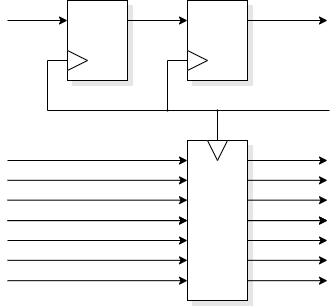

Let's assume we have an incoming signal with no timing relationship to

our local clock. We want so fix that: we need a synchroniser.

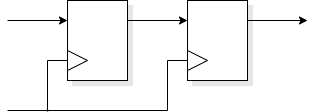

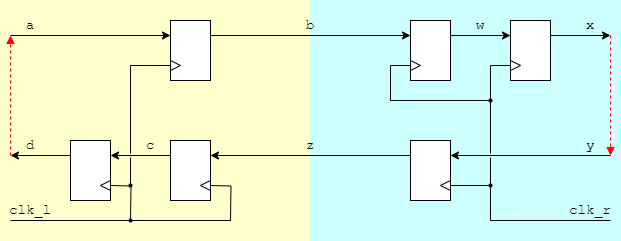

A typical synchroniser looks like this:

Operation is simple.

If the first flip-flop latches a valid level the second one copies

this one clock period later.

Else the first flip-flop may go metastable but has a whole clock

period to resolve to a digital state. As the violation is caused by an

input data transition the chosen state will determine whether the data

changed before or after the clock.

If determined that the data changed ‘after’ the clock then

it will be picked up on the next clock edge.

The first flip-flop probably doesn't remain metastable for a

whole clock period. The probability depends on the properties of the

flip-flop and the length of the clock period.

If the flip-flop doesn't resolve in time it will be forced to a

digital state on the next clock edge since the input has now

definitely had enough set-up time – but the second

flip-flop may go metastable if it was just resolving at the

inopportune moment. (The chance of this is

unlikely2.)

Paranoid designers may add more flip-flops. Each multiplies the

probability of remaining metastable by the same small number, thus if

(say) 1 in 106 is too high, go for 1 in 1012 , 1

in 1018 , etc. Each flip-flop (delay) also increases the

latency, of course.

There is no certain guarantee that this will always work.

However the probability of failure can be made very small.

[Remember that 3 GHz translates to 3×109

clocks/second or about 1019/century.]

Synchroniser flip-flops

Some cell libraries provide flip-flops specifically to address this

problem. They can still go metastable but they have a

‘steeper hill’ so they tend to resolve more quickly.

This is done by strengthening the gain internally, which makes them

slower (longer propagation delay) and probably raises power

consumption. Use them in the synchroniser role, if available,

otherwise stick to the ‘standard’ flip-flop.

Crossing clock domains

There are various possibilities for relationships between clocks.

- Synchronous circuits avoid this difficulty

- Isochronous circuits have a known, constant, phase relationship.

- Maybe with blocks with harmonic frequencies.

- This may be exploited (with care!) in inter-block communication.

- Asynchronous clock sources cause problems!

- Sending signals between asynchronous domains.

is impossible with 100% reliability.

- At some stage a flip-flop set-up/hold constraint will be

violated.

- We can make the probability of failure very

small†.

There is also the need for arbitration: which receiver

cycle did the data arrive in?

†Like very, very very small.

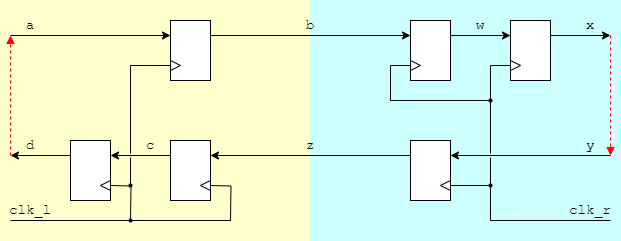

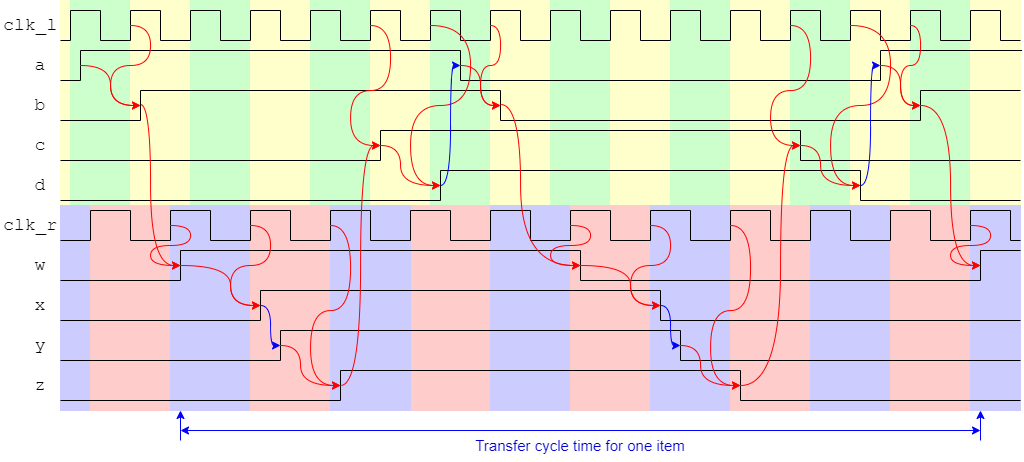

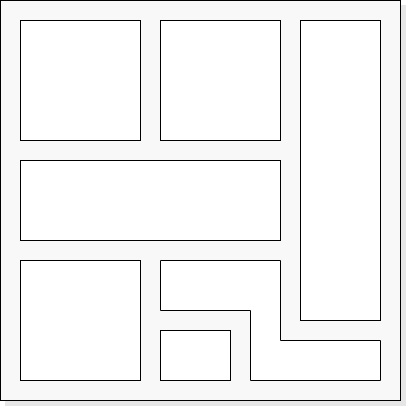

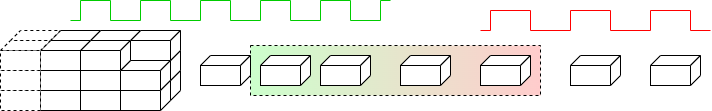

Synchronisation introduces latency. The probability of error decreases

(exponentially) with the time allowed to resolve any

metastability. This also slows down the communications.

The details may vary and there may be the possibility to optimise a

bit but the point to note is that the complete handshake needs

to synchronise twice – once on its way into each clock

domain – so the overall cycle time is slow. The exact latency

may vary depending on the clock's frequencies and phase difference.

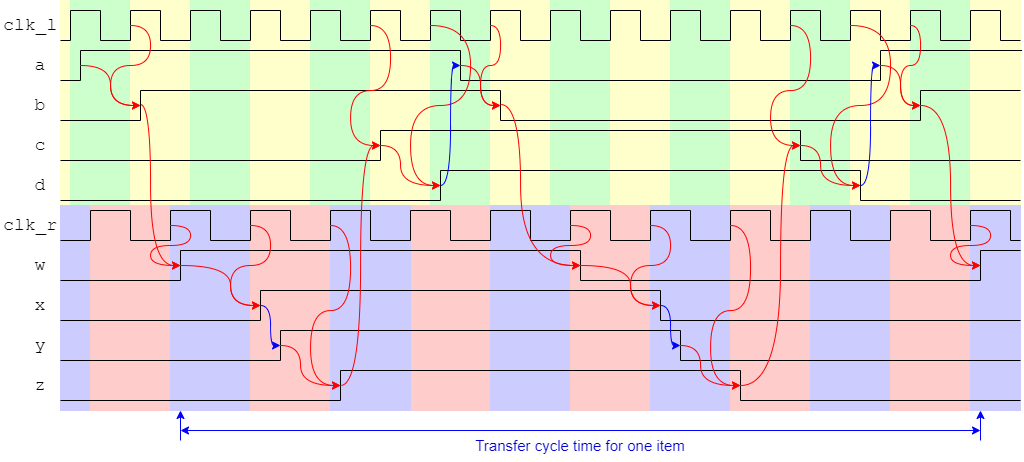

Optimisation?

Removing the flip-flops delaying

a⇒b

and

w⇒x

would reduce the cycle

time. ** DANGER **

If, as is likely,

w (for

example) is generated from combinatorial logic it could glitch to the

wrong value during evaluation. If such a glitch is captured by the

other clock, all sorts of problems may occur! The flip-flops filter

out any glitches.

Pragmatically

There is no need to synchronise every signal crossing a

boundary explicitly. If the timing is controlled only data validity

needs to be synchronised and any dubiously-timed data recaptured

during the synchronisation.

If the request is synchronised, accompanying data will have had plenty

of time to arrive.

When crossing a clock boundary, there is always:

- some latency

- a chance of failure due to persistent metastability

- small: may be reduced by adding extra flip-flops

- special flip-flops which resolve faster may be available

(though not from logic synthesis!)

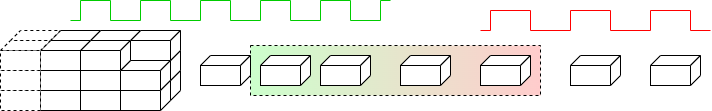

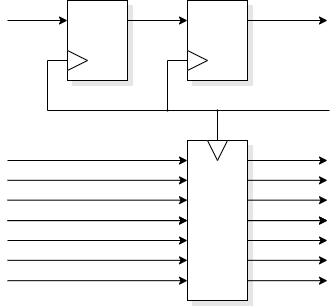

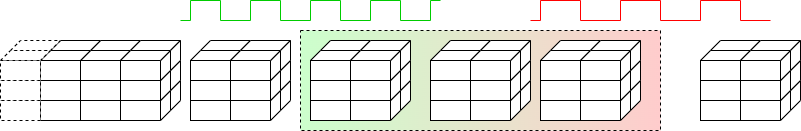

Some techniques for data domain clock-crossing

Synchronisers introduce latency and may ‘cripple’

performance:

Various solutions are possible, depending on requirements & complexity.

Synchronising every item: low bandwidth.

Buffer ‘packets’ of items: longer latency, higher bandwidth.

Read/write FIFO: low(ish) latency,

high bandwidth — more complex.

More buffers plus FIFO reduce waiting time: more complex still!

- Synchronising individual items independently is slow if there is

much to transfer: the latency is reflected in the bandwidth.

- Items may be ‘batched up’ into a buffer (takes some

time) and the whole lot synchronised together. This can be useful

in block transfers.

- With a stream of items the synchronisation latency of all but the

first item can be (partially?) hidden under the latency of the

first. The FIFO accepts items into a store synchronised with the

transmitter clock; these are verified separately internally and read

out using the receiver clock. When the buffer is partially full the

bandwidth is limited by the slower of the two clocks.

- Mechanisms may be combined, or others imagined …

Two modules at the same frequency with a phase difference

A common case met, for example, with an

SDRAM

interface.

SDRAM is manufactured using different process steps from logic chips

and is therefore supplied as separate dice. This means that there is

often a significant distance for signals to travel – e.g. across

a PCB – which causes a consequential delay, notably in

the phase of the returned data.

The SDRAM controller (at the logic end) therefore transmits its clock

to the SDRAM which uses that reference internally and sends a

reference signal back … which suffers a further delay, of

course.

The upshot is that the frequency data rate of returned data is

exactly known, but its phase is not. The data is first captured using

the returned clock reference and then resynchronised to the

internal phase through a short buffer.

As an auxiliary note, the SDRAM interface may run at a multiple of the

SDRAM controller's internal clock frequency to provide a greater interface

bandwidth but this will be an integer multiple with appropriately

managed phase.

It's also now common to use both clock edges as strobes

on the interface side to provide Double Data Rate

(DDR).

Two modules at the ‘same’ frequency – with

independent clocks

Sometimes it is expedient to have communications between units with

notionally the ‘same’ clock frequency although they have

different clock sources†. Examples may include

synchronous serial communication such as

PCIe

or S-ATA.

However, no two clocks will exactly match so one end of

the link will be faster than the other.

A mechanism to allow for this disparity is for the transmitter to

insert ‘comma’ symbols into the communications stream.

These carry no data, hence imposing a small overhead. The receiver

maintains a FIFO of incoming symbols which it is synchronising to its

own clock. If its clock is a little slower the FIFO will gradually

fill; if its clock is a little faster the FIFO will gradually

empty. When a comma symbol is seen, if the FIFO is getting close to

full the comma is discarded, saving some time and catching up;

conversely, if the FIFO is close to empty the comma allows the

receiver a slight pause. In this way the FIFO can be kept close to

half-full at all times and the communication maintained seamlessly.

†The jargon term is “plesiochronous”.

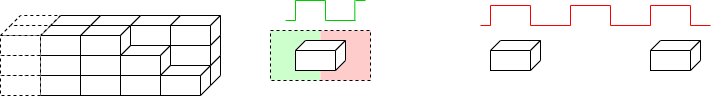

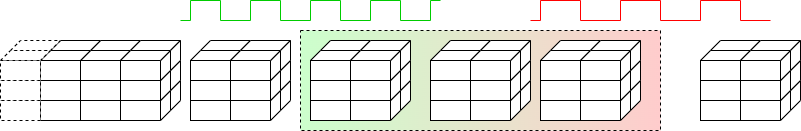

Buffering

A circuit can pass one ‘thing’ per clock cycle to another

circuit in the same clock domain.

Synchronising latency will apply to every ‘thing’ passed

across an interface between clock domains. This reduces the

communication bandwidth considerably (in things/cycle).

Here are a couple of (related) techniques to achieve higher bandwidth

across the interface.

Pack many bytes into a ‘thing’. Fill up a

‘bucket’ (RAM) of data then signal its transfer at the

end. There is one synchronisation penalty for the bucket-load which is

shared by all the data. The disadvantage of this is that the latency

is increased because the bucket must be filled then the transfer

requested, so the first datum takes longer to be received (although

they come close together after that.

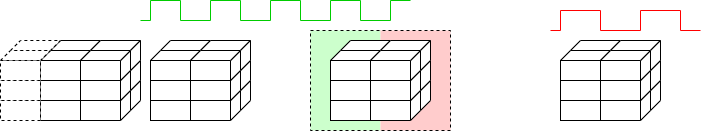

As above but double buffer. Fill up a bucket and notify the receiver

that it's ready. Whilst that is synchronising and being emptied, fill

up the next one. The disadvantage is that more (independent) RAMs are

needed; the advantage is increased bandwidth, closer to the maximum

rate (which is the slower of the corresponding processes).

A decoupling FIFO can extend the concept further. Conceptually

this is a bit harder to conceive. Think of a dual-port RAM (you could

build it out of flip-flops) where the transmitter writes to successive

locations and the receiver subsequently reads them at its own rate.

Every time a write completes a ‘counter’ is incremented

(Tx clock) and when a read completes it is decremented (Rx clock).

The control logic does need a synchroniser but synchronisation is not

necessary every cycle: for example if the FIFO contains four data,

following a read it contains at least three (more if writes are

ongoing) so no need to check before reading the next one. This can be

complicated to build but can offer close to maximum throughput with

close to minimum latency.

Back to timing closure.

Forwards to time stealing.

Up to Timing & Clocking.