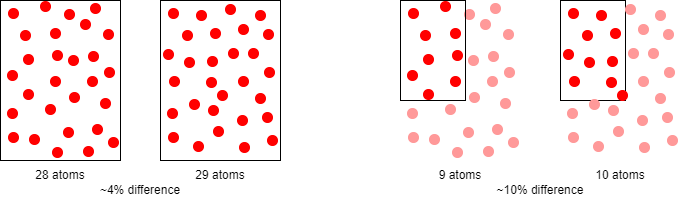

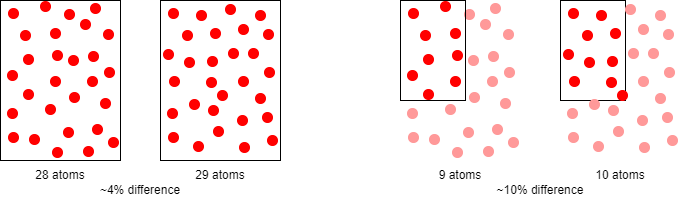

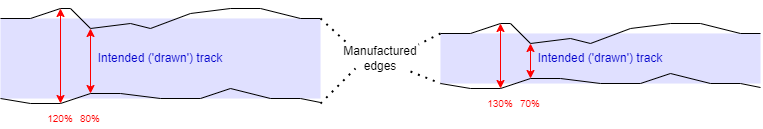

Maybe the biggest challenge to future devices is random variability in the manufacturing processes.

Guaranteeing the reliability of future devices may be difficult. One future challenge is making reliable computing devices from less reliable parts. This type of engineering is common in certain applications areas through the use of redundancy – for example a commercial aeroplane may have two engines but can fly with only one, engines being regarded as one of the less reliable components. (They also have multiple redundant instruments, hydraulics etc.)

Integrated circuits have been regarded as quite reliable (once the manufacturing ‘defects’ have been identified by testing and those chips discarded). The reliability of the tests is threatened (do you want something which ‘just passed’?) as is the production yield.

Two questions for the near future are ‘where it is appropriate to introduce redundancy?’ and ‘how should it be managed?’ It is easy to include more microprocessor systems in a Symmetric Multiprocessor (SMP), assuming that one or more may not work, and the software to handle this may be straightforward ... or not. Designing in redundancy at circuit level appears to be more difficult although this could be transparent to the software layer if achieved.

One place where redundancy has been used extensively is RAM, especially on server systems. Often error detection and correction codes (e.g. Hamming codes) are employed to increase the memory's reliability.

Figures from studies of DRAM error rates vary widely. Some of the worst-case numbers suggest perhaps a one-bit ‘drop’ (fault) in a gigabyte of DRAM every two hours. A typical cause is cosmic radiation. (Error rates on spacecraft are significantly higher!) See “ECC memory” for more details.

One trend is that the typical physical size of silicon die is shrinking – although capacity is still increasing. This helps in keeping an economic yield. A smaller die will, of course, still be able to accommodate significant functionality.

On the other hand, ever-larger systems are still made incorporating ever-inreasing funcionality.

“Yield” is the term used for the proportion of manufactured devices which are verified as functional. In the most part a single defect will render a chip useless. As defects are typically randomly scattered across a silicon wafer – and quality control means they are fairly rare – the chance of one killing a chip is (roughly) proportional to the chip's area. This means the yield is greater for smaller chips.

Example: say there are 20 defects across 1000 chips (the chance of two on one chip is small) the yield would be 98%. If the chips are twice the area the would be (500 - 20) / 500 = 96%.

Sometimes defective devices can still be put into service. Memory chips may have ‘spare’ rows of cells which can be mapped into place post-manufacture, or rely on ECC; some (e.g.) multiprocessor devices may be operable with a (small) proportion of broken subsystems. However many SoCs need to be defect-free and the yield† is very important,

Yield for a particular process typically improves after introduction as the foundry gets more familiar with that process.

†Often kept secret.

Up/back to roadmap index.

Forwards newer structures.