SystemVerilog

This is not a complete guide!

This is just here to give some glimpses at some SystemVerilog

additional features.

This is included here more for interest: you

don't need to learn this material but you are welcome to use what

you can if you wish.

You can find the full IEEE standard for SystemVerilog

(legitimately!) via the University's subscription to IEEE Xplore

For design-and-build

SystemVerilog

expands Verilog in numerous ways. A very useful addition is the

declaration (data type)

logic,

which is almost the same as

reg

(which, remember, is not always driven by a physical register)

but can be driven with

assign

too. This is one of the extensions you're most likely to encounter

first if you do this sort of thing in future.

Another new type is

bit

(it can still come in arrays to form variables); these bits always

have binary values and can't adopt

x or

z states.

| type |

Language |

Effect |

States |

| wire aaa; | Verilog | Declare a net: a combinatorial logic value. |

{0, 1, X, Z} |

| reg bbb; | Verilog | A signal which may (or may not) be state holding. | {0, 1, X, Z} |

| logic

… | SystemVerilog | Declare either a net

or a variable, depending on

usage. | {0, 1, X, Z} |

| bit

… | SystemVerilog | Like logic but can

only adopt one of two states. Can still be a multibit variable. | {0, 1} |

- A net is a signal which is not state-holding but can

always be derived from its inputs at any instant.

- A variable is state-holding: typically it is the

output of a D-type flip-flop/register.

These can be assigned by ‘Procedural

Blocks’ to help avoid pitfalls resulting from

potential ambiguities in its predecessor. For example

always_comb

can help to avoid accidental omissions in a sensitivity list, thus:

always_comb

a = b & c;

can replace

always @ (*) a = b & c;

(although there are some subtle

differences here, such as the former also executing at

t = 0).

always_comb

blocks are also sensitive to changes in inputs to any functions called

from within, while

always @ (*)

blocks are not.

This is restricted to combinatorial blocks. Presumably the

idea is to ensure only ‘proper’ code is enclosed, so

providing an additional security check. With

always_comb

the sensitivity list is inferred by the tools (plus a

‘bonus’ execution after

initialisation).

Plus, any particular assigned (written) value can only be assigned

within one such block.

(The Verilog language allows a variable to be written to in multiple

always

blocks: this is generally Bad Practice and will be rejected by

most/all(?) logic synthesizers.)

Danger: a ‘trap’ in Verilog

There is a nasty ‘trap’ in ‘old-fashioned’

Verilog style which, presumably, arises from it beginning as a

Hardware Description Language: this is the inadvertent

introduction of latches.

always @ (*)

if (X) a = b + c;

else if (Y) a = b - c;

Verilog acts as a programming language, where

a will not

change if neither

X nor

Y is

‘true’. This is ‘natural’ in programming but

assumes variable storage: when synthesized this means including

an extra latch structure, which is (almost certainly) unwanted,

and (definitely) expensive in area, power, timing and may introduce

timing (glitch) problems in implementation.

Logic synthesizers typically spot this issue and produce

‘Warning’ messages —

which developers typically ignore!

To avoid problems always include a definition for every output

state in a combinatorial logic description: if/when you don't

care, make this explicit and the synthesizer will (hopefully!) choose

the cheapest possible implementation. Thus:

always @ (*)

if (X) a = b + c;

else if (Y)

a = b - c;

else

a = 'hx;

// Don't care

It's strongly suggested this is applied as a

default:

in all

case

statements too, as a good habit.

Similarly there are also

always_ff and

always_latch

for registers and latches respectively, although these are (arguably)

less of a boon.

Finally (here) there is

final

which is the scheduler's complement to

initial.

This(/these) run(s) after a simulation has ‘$finished’. They can be useful for

(e.g.) outputting results and statistics or closing files. This is

only useful for test code, of course.

initial

in ASICs vs. FPGAs

initial

is used in verification code to run a thread at start-up time. When a

design is synthesised into an FPGA the synthesiser can interpret some

initial

statements and set up the contents of memories and the state of

registers and flip-flops. This is because these values are downloaded

when the FPGA is configured.

In an ASIC there is no downloading! Registers will not be

initialised and (in Verilog terms) start with a value

‘X’.

This can be very important when implementing state machines, et al.

where an active ‘reset’ is usually needed. RAM must also

be actively loaded; ROM contents must have been preprogrammed when the

appropriate macrocell was specified.

There are explicit enumerated types which save listing

definitions by hand.

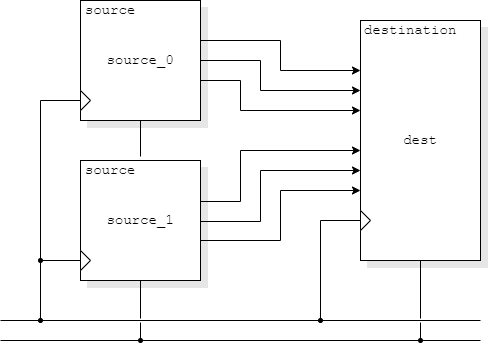

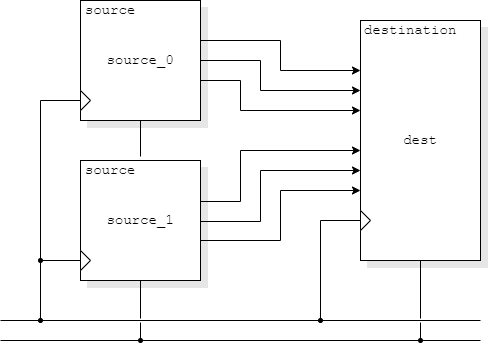

Interfaces

For large hierarchies the inter-block wiring can become very complex

with bundles of buses all heading in the same direction. In old-style

Verilog this gets complicated/messy/error-prone. Interfaces

provide a means of ‘wrapping’ associated signals into more

complex buses which can be connected as single units.

module top();

logic clk;

logic reset;

logic bits_0;

logic bobs_0;

logic pieces_0;

logic bits_1;

logic bobs_1;

logic pieces_1;

source source_0(.clk(clk),

.reset(reset),

.bits(bits_0)),

.bobs(bobs_0)),

.pieces(pieces_0));

source source_1(.clk(clk),

.reset(reset),

.bits(bits_1)),

.bobs(bobs_1)),

.pieces(pieces_1));

destination dest(.clk(clk),

.reset(reset),

.bits_0(bits_0),

.bobs_0(bobs_0),

.pieces_0(pieces_0),

.bits_1(bits_1),

.bobs_1(bobs_1),

.pieces_1(pieces_1));

endmodule : top

module source(input logic clk,

input logic reset,

output logic bits,

output logic bobs,

output logic pieces);

...

endmodule : source

module destination(input logic clk,

input logic reset,

input logic bits_0,

input logic bobs_0,

input logic pieces_0,

input logic bits_1,

input logic bobs_1,

input logic pieces_1);

...

endmodule : destination

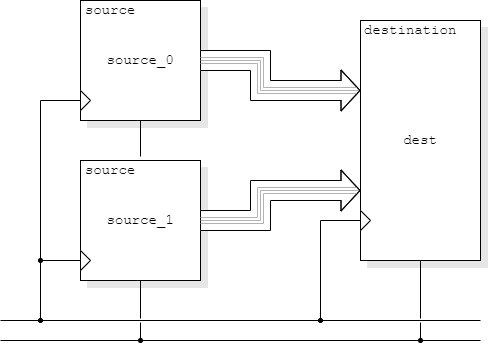

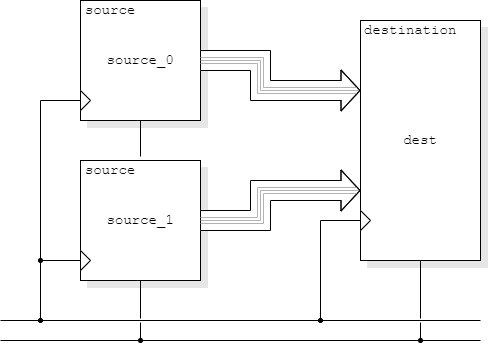

interface bundle;

logic bits;

logic bobs;

logic pieces;

endinterface

module top();

logic clk;

logic reset;

bundle stuff_0;

bundle stuff_1;

source source_0(.clk(clk),

.reset(reset),

.stuff_out(stuff_0));

source source_1(.clk(clk),

.reset(reset),

.stuff_out(stuff_1));

destination dest(.clk(clk),

.reset(reset),

.stuff_in_0(stuff_0),

.stuff_in_0(stuff_1));

endmodule : top

module source(input logic clk,

input logic reset,

bundle stuff_out);

...

endmodule : source

module destination(input logic clk,

input logic reset,

bundle stuff_in_0,

bundle stuff_in_1);

...

endmodule : destination

Access to the fields within an interface follows the convention you

might guess at. Thus, for example, in the instance

dest above,

fields can be broken out as

‘stuff_in_0.bits’,

‘stuff_in_0.bobs’

etc.

Structures

Interfaces bundle together associated wiring so multiple buses

can be handled as one entity. Structures serve a similar role

for other elements, such as associated registers. The syntax is very

C-like and should be more or less intuitive for anyone used to

programming.

struct { bit [7:0] opcode; bit [23:0] addr; } IR;

(Nicked definitions from standard.)

typedef struct {

bit [7:0] opcode;

bit [23:0] addr;

} instruction;

// Type defined

instruction IR;

// Stucture variable defined

Arrays

Verilog syntax can be both somewhat confusing and somewhat restrictive

in this area. SystemVerilog at least alleviates some of the

restrictions! First, some terminology:

- An array can be packed

logic [31:0] data;

- or unpacked

logic memory [0:1023];

In both cases the index is expanded across the specified range. The

index can be ascending or descending although it is typically

conventional to number bits-in-a-bus, at least, in a descending

(little-endian) sequence.

A one dimensional packed array (as

here) is sometimes called a ‘vector’. Only certain

data types may be ‘packed’ although these are the elements

you might expect, such as

reg,

logic etc.

The two types can be combined, such as:

logic [31:0] mem [0:1023];

which declares a 1 KiW memory of 32-bit words. Access is then

available with statements such as:

data = mem[addr];

… and this is sometimes referred to explicitly as a

‘memory’.

SystemVerilog allows more detailed indexing so that (for example) a

byte could be extracted from the memory:

data = mem[addr][15:8];

(Note the position of the indices!)

It is possible to have – and combine – multiple packed and

unpacked dimensions in arrays. This can get quite confusing, so

don't be too tempted and take care (and read the documentation!)

before getting in too deeply.

Nesting

SystemVerilog allows modules to be declared within other

modules, limiting their scope accordingly.

Did you know …

Verilog can ‘get at’ any signal using the

appropriate hierarchical name

(with

‘.’

separators).

local_signal = module_X.submodule_Y.signal_of_interest;

This can be handy in verification to ‘probe’ the insides

of nested modules – perhaps with some logic functions.

For verification

The improvement is testbench facilities is probably the most

significant addition. These include (presumably) familiar concepts

such as object-oriented programming and string handling.

Debugging is eased with

assertions (also present

in some earlier Verilog extensions, but not as formalised).

Debug suggestion

Typically bus signals ‘hang around’ even when not in use:

for example a memory address will possibly remain on the address bus

after a transfer is complete. For display and

verification (only) it can be convenient to highlight

the value only during the actual transfer.

A means of doing this is to create (within the testbench) some extra

signals for display purposes. Something like:

assign disp_address = (read || write) ? address : 'hXXXX;

This makes the signal ‘undefined’ (you could choose

Z

if preferred) when not in use which makes the transfers much more

obvious in a trace.

Miscellaneous

Lots of syntactic features (such as

‘x++’)

now work the way you might expect; loops can

break or

continue

and so on. There's plenty more detailed stuff if interested and not

enough time/space here to delve into it all.

Up to Verilog index

Onward to assertions.