This is not a complete guide!

This is

just here to give some glimpses at some of the capabilities of

assertions, particularly for verification of designs

in SystemVerilog.

Assertions are run-time checks for errors which appear in many variations in different language environments. In one way assertions can be coded with existing tools but nowadays there is sometimes better support within the language environment.

As a rough classification, consider a software example where an index might put an array reference outside the array.

Assertions should be able to raise the confidence that code works without needing to impact the final performance.

In hardware terms we are primarily concerned with verification – finding faults before implementing and deploying the device. This is where assertions can provide a significant confidence boost.

This is an overview of the SystemVerilog facilities.

It is here to give a starting point; refer ro something more

definitive for fuller details.

(The description in the standard is 118 pp.)

Some associated keywords are:

There are two types of SystemVerilog assertions: Immediate Assertions and Concurrent Assertions.

Immediate assertions are fairly straightforward: they are ‘immediate’ in the sense that they are not dependent on time. They can be used for things like checking values or signal combinations.

always @ (aa, bb)

if (aa && bb) // Nothing

$display("Signals aa and bb clashed");

always @ (aa, bb)

assert (!(aa && bb))

else $error("Signals aa and bb clashed");

If the else is omitted the tool will call $error by default, although with less information.

Note that the assert

can have an action before the

else which

is executed each time the assertion is satisfied. An example function

would be counting the number of times this has happened.

It's also possible (and sensible!) to give the assertion a name

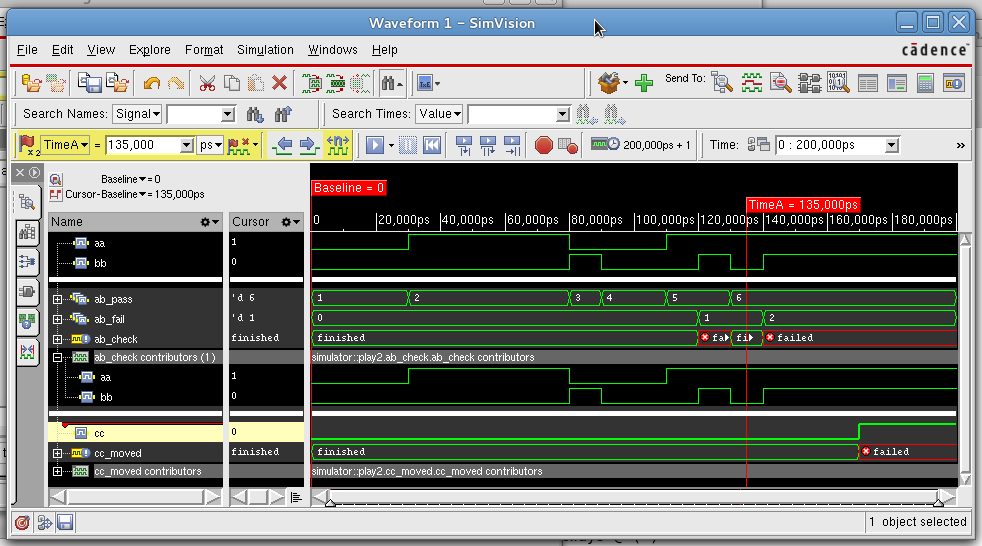

so it can be identified in a wave trace.

…

always @ (aa, bb)

ab_check: assert ((aa && bb) != 1) ab_pass++; // Count sucesses

else begin

ab_fail++;

// Count failures

$warning("ab fail at %t.", $time);

end

always @ (*)

cc_moved: assert (cc == 0) else $info("cc went high!");

…

(Click to enlarge figure.)

…

ab fail at 120000.

ab fail at 140000.

cc went high!

…

The system tasks $info, $warning, $error and $fatal are all ‘print’ outputs, intended for increasing severities of concern.

An assert is a statement, like any other, and needs to be told when to execute: the example above is sensitive to changes in aa and bb so it will be active throughout a simulation run. However a simulation may be halted on the occurence of a failed exception of sufficient ‘severity’ such as an $error but not a $warning.

assume is similar to assert in simulation but has added properties for formal verification.

Immediate assertions happen when they are triggered by an event, such as a signal change. Concurrent assertions check behaviour repetitively, across time, using sampled values. As such they require some sort of timing reference – i.e. a clock. This will often be a/the system clock (but need not be) but should provide some sort of countable cycles.

As might be expected, there is considerable associated syntax which can provide an extensive range of facilities. Let's start with a simple, illustrative example, requiring only a few new functions.

…

example: assert property(@ (posedge clk)

disable iff (reset)

req |-> ##1 ack)

else $error("Check failed");

…

This therefore asserts that, as long as we are not being reset, if req is active at one clock edge ack is expected to active at the next. This is illustrated in the trace below.

There is a plethora of accompanying ‘new’ syntax: here are

some more salient items.

The |-> implication starts timing (counting) in the cycle(s) the implication is true. There is also a |=> implication which starts one cycle later. “|=> ##n“ ≡ “|-> ##(n+1)“

The delay operator (“##n“) can also specify time ranges: “##[m:n]“.

You can have sequences on either side of implication operator,

thus:

“req ##1

grant |-> ack ##1 !ack“

System tasks

“$stable()“,

“$rose()“

and

“$fell()“

allow changes in signal states to be detected whilst a concurrent

assertion is active.

BEWARE! Such changes are detected by comparing

samples at the chosen sample clock: they are not specified to

spot a short glitch if it occurs entirely between two

samples.

The system task

“$past()“, allows expression from previous samples.

What else is worth including here?

(Work in progress!)

Back to general SystemVerilog

Up to Verilog index