The normal clock source for digital logic is a crystal-controlled

oscillator. These use vibrations in a carefully machined (piezo

electric, usually quartz) crystal to stabilise an electrical

oscillator circuit. Without any special care a frequency within about

50ppm† is usual. If it matters, much greater

stability is, of course, achievable as is demonstrated by

‘quartz clocks’.

- No two independent oscillators will run at exactly the

same frequency.

- If a constant phase relationship is required a single oscillator must

be used.

†Equivalent to about 4 s error per day.

Frequency examples

- Digital logic is operated at frequencies of several GHz

- For ASIC design, typically think 100s MHz

- Humans tend to prefer simple numbers such as 20 MHz

- A ‘serial line’ (old fashioned now) has standard baud

rates of 9600, 19200, 38400, 115200 … Hence multiples of such

frequencies are not uncommon.

- Example: 18.432 MHz = 30 × 16 × 38400 =10 × 16 × 115200

- USB uses bit rates of 12 Mb/s (USB 1), 480 Mb/s (USB 2)

- In I/O applications there is commonly some tolerance.

- E.g. RS232 ± a few percent

- USB 480.00 Mbit/s ±500 ppm,

12.000 Mbit/s ±2500 ppm

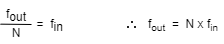

Frequency and phase

It's only meaningful to talk about frequency with respect to

repetitive signals.

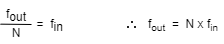

The frequency of a clock is the reciprocal of its period.

f = 1⁄T

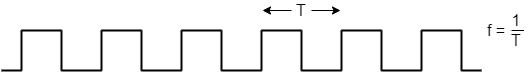

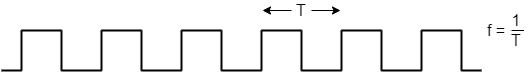

With two or more signals there may be a phase relationship.

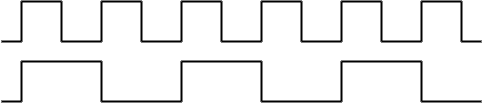

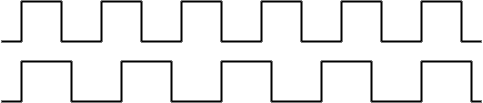

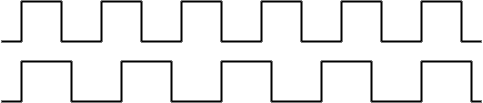

Same frequency, different phase.

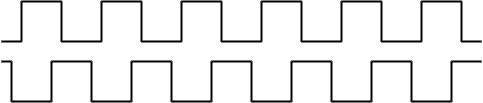

Harmonic frequencies (phase relationship is fixed)

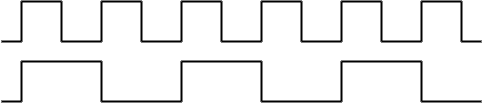

Non-harmonic frequencies: phase relationship drifts

It is increasingly common to have blocks running at different

frequencies. This is sometimes referred to as GALS

Globally Asynchronous Locally Synchronous.

Or possibly the same frequency, but ‘uncertain’ phase.

- Sometimes just reduce (divide) master clock

- Sometimes have separate clocks.

Clocking, frequency and power

The majority of the power dissipation in CMOS logic is dynamic,

i.e. it occurs when gates/wires switch. Thus – when

executing – the power dissipation is roughly proportional to the

clock frequency. Reducing the frequency saves power (dissipates less

heat).

The clock network is a significant source of power dissipation. The

power used is (effectively) proportional to clock frequency. Thus it

makes no sense to clock a circuit faster than is necessary. Clock

gating may be introduced to stop clocks when a block is unused

– but this should be done with caution!

Clock Gating

If part of a device is not in use, its clock may be stopped

(‘gated’). This is more power-economic than simply

‘disabling’ the registers because it prevents (parts of)

the clock tree from switching.

However there are several concomitant hazards and it's easy to

introduce unpleasant clock skew or even glitches if care

is not exercised. Don't do this ‘by hand’ until you've

lots of experience!

Implementing clock gating is best left to the tools (if

available). Note that adding gating may compromise peak performance

so is not always desirable.

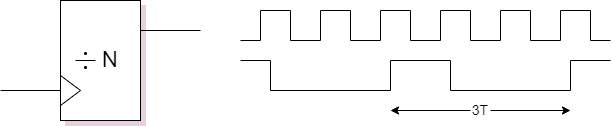

Changing frequency

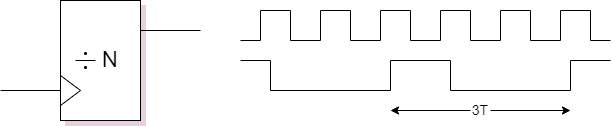

Reducing frequency – by an integer factor – is easy.

Reducing frequency – by an integer factor – is easy.

- Note that dividing by an odd number will result

in an uneven duty-cycle

- This may or may not matter to you

- The output clock will have a fixed (unknown) phase relationship

with the input.

Increasing frequency is more difficult: use a Phase-Locked Loop (PLL)

These include some mixed-signal (analogue) components …

… but can usually be bought-in from a specialist designer.

Why bother?

- It is difficult to carry UHF signals across a PCB; great care with

tracking is required.

- Switching signals dissipates power. The more you switch, the more

it costs.

- Switching signals transmits Radio Frequency Interference (RFI).

(Where do you think the power goes?)

This is a Bad Thing, and may be illegal.

- Generating stable clocks at UHF directly is impractical.

A typical clock source will be a crystal controlled oscillator. These

are cheap and quite precise. Frequencies of the order 1-100 MHz

50ppm are readily available. However modern computers are typically

clocked much faster.

So, the usual ploy is to supply a stable frequency (say 20 MHz)

to the chip and then multiply this on board to the desired clock rate.

A bonus from this strategy is that the clock multiplier is digital and

can be controlled (e.g. in software) allowing a trade-off between

performance and power consumption.

Another strategy is to reduce the clock rate – to reduce power

dissipation – if the chip is becoming too hot.

Phase-Locked Loops (PLLs)

A PLL is a machine

capable of matching the frequency of an input signal.

Everyday example

Consider a television set. It must display images at the same rate as

they are broadcast. Thus it needs synchronisation information so that

it can adjust its internal timing to match the transmitter. Of

course, in modern sets at these slow speeds this can be done digitally

by varying the number of ‘local’ clock cycles in each

line, frame, etc. slightly.

You can see this in the lab. (phase 3) with the

‘sync.’ signals running to(wards) the monitor.

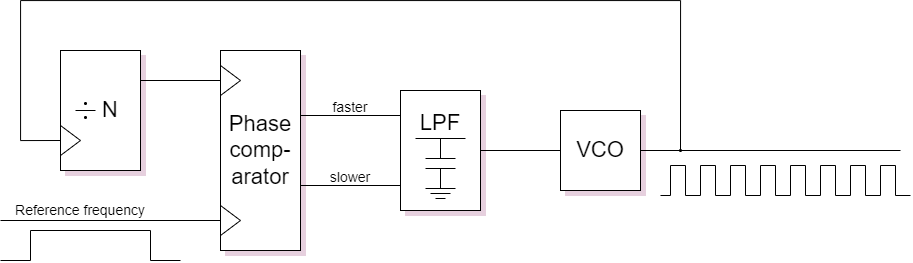

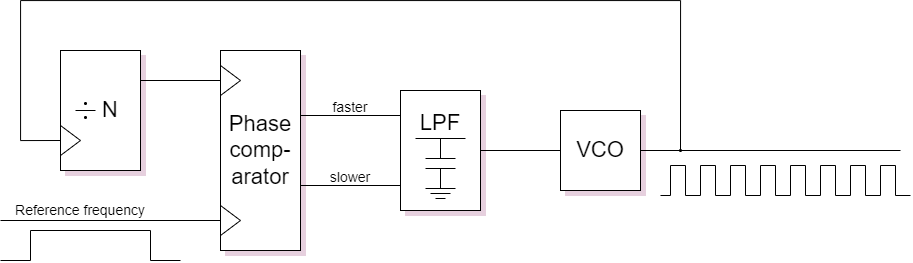

Clock multiplication

The figure above shows a clock multiplier which works by matching a

division of an output clock to an input reference.

LPF – Low Pass Filter

A typical phase comparator produces pulses on its outputs which

indicate which input edge came first. These need integrating

(smoothing) to produce a voltage which is (approximately) stable over

many clock periods.

VCO – Voltage Controlled Oscillator

An oscillator which runs ‘naturally’ in a certain range of

frequencies which is ‘tuned’ by an analogue input voltage.

Because a PLL circuit is controlled by feedback its output frequency

will vary slightly around the nominal frequency. This contributes

to clock jitter – the perceived variation in clock

frequency. Jitter is a Bad Thing because the logic must always

evaluate within the shortest clock period (not the

average) and the more variation there is the shorter this minimum time

will be.

Definitions to remember

- Skew: the difference in arrival time of a signal at different

destinations.

- Clock jitter: the variation of a clock frequency around its

specified value.

Back to time stealing.

Forwards to other timing stuff.

Up to Clocking.

Reducing frequency – by an integer factor – is easy.

Reducing frequency – by an integer factor – is easy.