As far as physics currently understands time is a single continuous dimension.

Simulation time is discrete but multidimensional! (Short aside: Event Driven Simulation.)

Naturally, none of this relates to the actual time taken to run the simulation, which depends on how much switching activity takes place in the design.

always @ (posedge clk) a = b; // Blocking

always @ (posedge clk) b = a; // Blocking

always @ (posedge clk) x <= y; // Non-blocking

always @ (posedge clk) y <= x; // Non-blocking

After a clock edge:

However:

is entirely predictable – if rather pointless.always @ (posedge clk)

begin

a = b;

b = a;

end

always @ (posedge clk) x <= a; // Non-blocking

always @ (posedge clk) a = b; // Blocking

In simulation x will always take the value from b.

However a synthesizer will probably see this as two sequential flip-flops.A synthesized circuit will behave differently from the simulation!

Okay, that's the wrong thing to happen but complaining won't change it.

† [Forward reference]

When simulating synchronous circuit models the most convenient thing to write is:

always @ (posedge clk)

if (count < 9) count <= count + 1; else count <= 0;

‘count’ then changes:

The resulting trace may be slightly misleading although it is safe.

But what if the inputs (RHS) are generated with a blocking assignment ...

Therefore keep all blocks and modules in the same style!

(Perhaps) the obvious way to stimulate a design may be something like this:

initial clk = 1;

always #5 clk <= !clk;

initial

begin

data = 0;

#10;

data = 1;

#10;

data = 2;

#10;

end

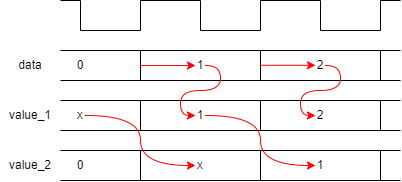

always @ (posedge clk) value_1 <= data;

always @ (posedge clk) value_2 <= value_1;

Unfortunately – because the blocking assignment (data) completes before the non-blocking assignments – this will lead to the following timing relationship:

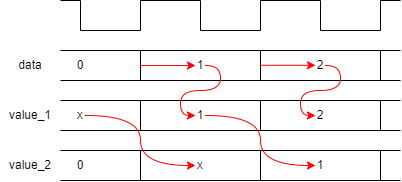

Offsetting input changes slightly from the clock may help.

parameter period = 10; // Makes changes easier

initial clk = 1;

always #(period/2) clk <= !clk;

initial

begin

#1; // Inputs delayed

data = 0;

#period;

data = 1;

#period;

data = 2;

#period;

end

always @ (posedge clk) value_1 <= data;

always @ (posedge clk) value_2 <= value_1;

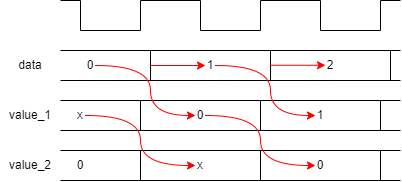

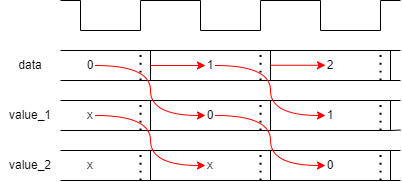

There are a couple of disadvantages of the form above.

parameter period = 10; // Makes changes easier

initial clk = 1;

always #(period/2) clk <= !clk;

initial

begin

data <= #1 0; // Inertial delay

#period;

data <= #1 1;

#period;

data <= #1 2;

#period;

end

always @ (posedge clk) value_1 <= #1 data;

always @ (posedge clk) value_2 <= #1 value_1;

The evaluation here takes place at the clock edge: it is just the

result assignment which is delayed.

Suggest that this is clearer!

Rather than inserting explicit delay times it may be more robust to count the clock edges. The ‘@’ symbol means ‘at the next event from the following list’ so: ‘@ (posedge clk)’ means ‘wait until the next active clock edge’ — this will always keep execution in synchronisation with the clock.

‘repeat (10) @ (posedge clk)’ will, of course wait for the tenth successive clock edge etc.

Here are some convenient methods:

#20 a = l; // Delay in execution of sequential block

wire #4 q; // Declare a ‘net delay’ ...

assign q = a & b; // q changes 4 timesteps after an input change

register <= #10 input_value; // Propagation delay on signal

Time is modelled in two ways:

Examples:

initial

begin

a = 0;

#10;

a = 1;

end

assign b = !a; assign c = !b;

| Time | action |

|---|---|

| 0 | a = 0 |

| 0 | b = 1 |

| 0 | c = 0 |

| 10 | a = 1 |

| 10 | b = 0 |

| 10 | c = 1 |

At any point there is only one thing which is scheduled to happen, but a change schedules a(n immediate) change on b, etc.

initial

begin

a = 0;

#10;

a = 1;

end

assign #5 b = !a;

assign #6 c = !b;

| Time | action |

|---|---|

| 0 | a = 0 |

| 5 | b = 1 |

| 10 | a = 1 |

| 11 | c = 0 |

| 15 | b = 0 |

| 21 | c = 1 |

Delays can alter when switching occurs.

Delays can also be inserted within assignments to delay the assignment without retarding the flow of execution, e.g.:

a <= #10 b;

For added veracity it is possible to specify different rising, falling and turn-off delays for a signal by listing these in brackets. E.g.

#(3,2)

means a rising delay of 3, a falling delay of 2. The turn-off delay has not been specified so defaults to the minimum of these (if appropriate).

‘Glitches’ are brief signal changes which result from signal races through combinatorial logic; they will only be visible in simulation if gates (or other logic blocks) include delay models. Thus they will not (typically) appear in an abstracted simulation.

Glitches may appear in more detailed models, including a netlist extracted from a synthesized design: i.e. one which includes details of the actual circuits and delays. This could cause problems running the same simulation successfully as previously, depending on how the testbench is constructed. There is a little bonus page about this here.