Implementation and Design trade-offs

Q. Given a specification how do you find the perfect implementation?

A. There is no such thing!

- There are numerous ways of making something which works.

- (There are many more ways of making something

which doesn't work!)

Consider the implementation (largely) in a top-down fashion

- Algorithms

- Architecture

- RTL

- Practicalities

- power supply

- cooling

- pad limitations

- …

The ‘right’ algorithm

In this module we are assuming that the algorithm and the higher

levels of the architectural design are fixed and we concentrate on the

implementation. This section covers the microarchitecture and the RTL;

circuit details are left for later.

It is very important to choose an efficient algorithm. For example, to

choose what is likely to be a software exemplum, searching 1000

records in a linear table may require an average of 500 comparisons

whereas in a binary tree they may only average 9 (slightly more

complex) tests.

However clever the later implementation it is unlikely to compensate

for such a crushing disadvantage.

Top-down design?

So the principle is that top-down design is usually the best way to

go.

However, it is important that when it comes to implement the algorithm

this is possible at reasonable cost. Plotting a circle may look simple

using sines and cosines but calculating these ‘on the fly’

may be prohibitive. Therefore it is a good plan to look ahead and

consider the likely implications before finally committing to an

implementation plan!

Example: Bresenham's line algorithm

Perhaps the ‘obvious’ way to draw a line is to use an

equation such as:

y = mx + c

and then, by iterating over x work out each y position then round it

onto the nearest pixel. This requires the determination of the

(fractional) m and c (by division) and a multiplication for each pixel

plot. Because ‘real’ numbers are only approximated the

result is subject to (rounding) errors.

Bresenham's algorithm plots the closest possible pixels to a specified

line without using (expensive) multiplication or division. It does not

require floating point representation and it does not suffer from

rounding errors.

Example: The Fast Fourier Transform

First, if you don't follow the technical details in this box, don't

worry. It is simply an example of how the algorithmic

level can be the most important place to perform optimization.

The Fast

Fourier Transform (FFT) – in computer terms usually

attributed to Cooley and Tukey (1965) but the principle stretches back

much further – is a means of optimizing a Discrete Fourier Transform

(DFT) by combining redundant operations. The Fourier transform is a

means of determining the spectral components of a signal – akin to

finding the volumes of the notes which make up a chord.

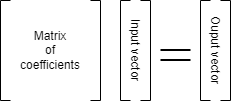

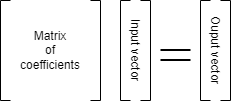

A discrete Fourier transform represents an input by a set of

samples and produces an equal number of results. Better resolution is

achieved by processing more samples. In its simple form a DFT can be

represented by a matrix multiplication.

Clearly this can involve a lot of multiplication. The complexity is

N2 , where N is the number of samples.

The FFT exploits redundancy in the coefficient matrix to reduce the

number of calculations. The complexity of a comparable FFT is

N.log2(N).

| N | N2 | N.log2(N) | Saving |

| 8 | 64 | 24 | 62% |

| 32 | 1024 | 160 | 84% |

| 256 | 65536 | 2048 | 97% |

| 1024 | 1048576 | 10240 | 99% |

This table shows the sort of savings which can be made. Where such

things are possible they can vastly outweigh any optimizations in

later implementation.

The point is that the algorithm is the first, and often

the best, place to optimize.

Design trade-offs

- There are many ways of producing a correct design.

(There are even more ways of producing an incorrect one.)

- The ‘best’ design for your application will be

influenced by numerous different factors:

- Speed

- Power

- Size

- Simplicity

- Most of these rely on skill and judgement in the first instance.

- Later it is possible to get better estimates from tools.

- RTL allows immediate feedback on cycle counts.

- Experience (or experiment) suggests what may be

feasible in a cycle.

“On time, on budget, working; choose any two.”

Speed

In one respect, ‘the faster, the better’ is a reasonable

design philosophy; after all it is easy to reduce the clock rate to

slow an implementation down, but the maximum frequency cannot be

exceeded.

However there are often ‘real time’ constraints which need

to be met, but not exceeded. A real-time circuit needs to guarantee a

minimum worst-case performance. For example, there is unlikely to be a

benefit in an MP3 decoder being able to go faster than is needed to

play a particular track.

Increasing speed beyond a certain level is likely to require a larger,

more complex, power-hungry circuit.

Power

Reducing power consumption is important, particularly in

battery-powered equipment. Power consumption is (loosely) related both

to the size of the device and its speed. Generally, more logic means

higher power consumption as does going faster. Note, however, the

difference between power and energy.

- Energy is the limited resource stored in the battery.

- Power is how fast energy is ‘used’ over time.

Thus, a circuit which computes at double speed but halts for half the

time will use (roughly) the same energy as one which consumes half its

power all the time. (There can be some more subtle trade-offs made in

this area.)

Remember that the power which is dissipated emerges as heat and this

has got to be extracted. Low power therefore can mean better even for

‘tethered’ equipment, by alleviating the need for fans,

allowing boxes to be sealed, running cooler (extending product

lifetime) and, of course, reducing the electricity bill.

Size

Depending on the application, it may be better to produce a small

chip. Chips are manufactured on silicon wafers and the cost/wafer is

roughly fixed. A naive approach would suggest that a chip of half the

area would therefore cost half as much.

However, because there is only a certain yield of functional

chips which is governed by the density of defects on the wafer, a

functional chip of 10 mm2 will cost less than half one

of 20 mm2 . For a device that is to be mass marketed,

size can be critical.

When implementing on an FPGA what matters primarily is that the design

will fit. However FPGAs come in different sizes (and prices) so a

small size usually means a cheaper product.

Even then an FPGA will come with certain resources (such as RAM or

multipliers) on board. If these can be exploited there may be savings

on flip-flops or logic.

Simplicity

A simple design is likely to be small, which is a benefit in

itself. However design simplicity brings other benefits. Primarily, a

simple design is easier to build – and much easier to

test and debug – which reduced development time and cost.

Reduced development time means the product is marketed sooner which

brings disproportionate gains in sales. Product reliability helps gain

future sales – or, rather, unreliability loses them.

The enemy of simplicity is the need for more (or better) features. For

example HDTV processes more pixels per second than older standards so

the decoder has to work harder, perhaps demanding a faster or more

parallel architecture.

Trade-offs: links

In this session

Other

Conclusions

- There are many factors to consider when setting out to build a system

- You probably won't find ‘the optimum’ solution …

- is it worth trying?

- will the ‘goalposts’ move?

- there are probably things you don't know

- … but you should aim to get close

- Your design constraints may differ from project to project

- speed is tempting but fast enough is fast enough

- power (energy) increasingly important – more later

- area smaller is probably better

- simplicity improves time to market (or

‘reliability’)

Next session's notes: timing.

A little bonus postscript.

Time to market

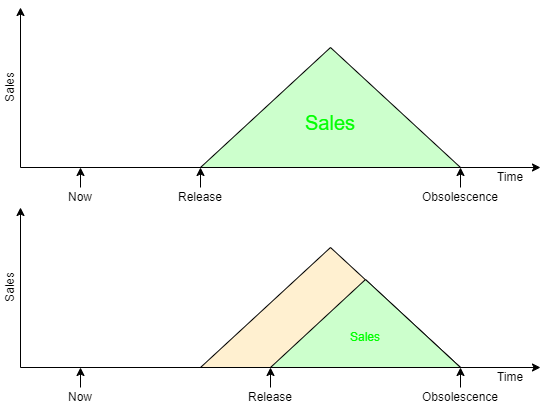

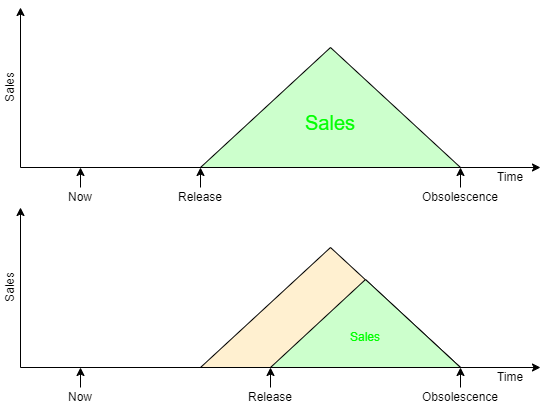

Microelectronics is a fast moving milieu. The release date of a

product is as important as its functionality. A particular device is

going to be obsolete in the near future; sales have to take place

before then.

On the right is a sketch suggesting how development time affects overall

sales, represented by the green shaded areas.

The point being, a small difference in development time can make a big

difference in profit so designer productivity is a key factor in the

industry.